Marla Runyan is the first legally blind athlete to compete at the Olympics.

MARLA RUNYAN was inspired by the Olympics from a young age but had no idea she would one day compete in them and certainly not in the circumstances in which she did.

At the age of nine Marla was diagnosed with stargardts disease, leaving her legally blind and those around her worried about the restrictions it would put on her life. Marla had other ideas. She refused to give up on her dreams or to see the disease affecting her as a disability. She went on to to excel academically and also on the track where she was dedicated to being the best and fueled by the doubt others had in her.

In this exclusive interview we talk to Marla about where her positivity comes from, some of her greatest achievements in running and her work as a teacher.

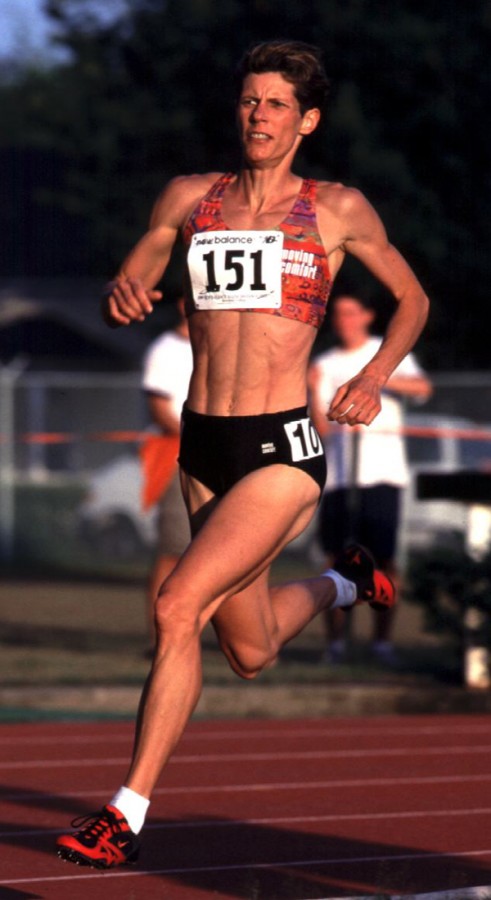

Marla has dedicated much of her life to training and competing in athletics on the world stage (photo THOMAS BOYD/The Register-Guard).

When did you first get involved in athletics and were there any particularly strong influences early on in life?

I was involved in a variety of sports as a child; swimming, gymnastics, and soccer. If I wasn’t in an organised sport, I was usually outside playing with the neighbourhood kids. I was always on the move.

My first experience with track and field came at age ten when my parents signed me up for a kids community track program. The event I loved the most was the high jump. My dad actually built me a high jump pit in our backyard. It wasn’t much – just some left over lumber for the standards, a PVC pipe for the crossbar, and some old mattresses for a soft landing. But I loved it.!

I have always loved the Olympics. I remember watching the 1976 Olympics on TV – and watching Nadia Comeneci score perfect 10s and win gold. I watched the Games again in 1984 and I remember watching Dwight Stones set the American record in the high jump at the Olympic Trials.

Since the ’84 Games were in LA, I actually got to stand on the marathon course and watch as the marathoners ran by. I had no idea that 16 years later I would be running in the1500 meters at the 2000 Olympic Games, and that I would later run marathons. At that time, I thought of myself as a high jumper. The Olympics was always my inspiration.

How did finding out you were going blind affect your ambitions for sport and what you were doing at the time?

When I was diagnosed with stargardts, it felt like the expectations around me just fell. No one really expected me to do much. Before that time, I was expected to be a good student, to go to college, and so on. But after the diagnosis, it was like, “Marla, just do your best”. This really angered me. My reaction was to push myself even harder, to hold higher expectations for myself than what others held for me, and to prove to others that I had value and that I could excel.

While I was a straight ‘A’ student in high school, the track ultimately became my venue to prove myself. The track was everything I was about: challenge, accountability, determination and competition. My reaction to losing my sight was to run.

Marla Runyan running in the 1500m race at the 2000 Olympic Games, Sydney, Australia (photo Brian J.Myers@Photo Run).

Could you tell us about the Paralympics in 1992 and did you expect to win the medals you did?

Throughout my years as an athlete, I competed against fully sighted runners. I ran on my high school and college track teams, and after my collegiate eligibility was over, I continued to train on my own with the goal of qualifying for the 1996 US Olympic Trials.

I had very little involvement with sports for the blind, and therefore, I did not even know about the Paralympics until 1990. I decided to check it out. I qualified for the 1992 Paralympic Games, however, the only track and field events offered in my disability classification were the 100m, 200m, 400m and long jump.

My performances as a post-collegiate athlete broke the existing world records for these events within my disability classification (B3). For the most part, I expected that I would win gold in those events, but you really never know for sure.

Eventually, I set world records in the B3 classification for every distance from the 100m to the marathon, as well as the high jump, long jump, and pentathlon.

In 2000 you competed in the Sydney Olympics. How did it feel to be the first legally blind athlete to compete in the Olympics and also to be the highest placed female American in your event?

I don’t really get too caught up in titles and statistics. It never occurred to me that by making the US Olympic Team, I would become the ‘first legally blind Olympian’. Honestly, that thought never entered my mind, and it was certainly not my motivation.

That title was really just one of those stats that you learn about after the fact. It was never the reason I pursued the Olympics. My motivation was to reach my potential as a runner, and if I could do that, I believed I could run fast enough to make the team. I had no idea of the events that would follow as a result – the media frenzy, a book deal, speaking engagements, and so on.

For me, my eighth place finish at the 2000 Olympics was a disappointment. I had hoped to run faster and place higher. Even though no other American female had finished higher in that event at that time, that didn’t matter much to me. I still believe I could have run a smarter race, and I believe if I had done some things differently in my training, I could have performed much better at the Games.

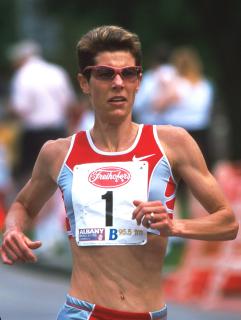

As well as her accomplishments on the track Marla is also know for her success in the New York Marathon.

You had phenomenal success in the 2002 New York Marathon taking the top American finish. How did you prepare for the marathon and how did it feel getting over that finish line in such a remarkable time?

In 2002, I ran two hours 27 minutes, ten seconds in the NYC Marathon which earned me a fourth place finish overall. My goal going in had been to run two hours 28 minutes, which is an average of 5:40 minutes per mile. This was the pace I trained to run, so I was pleased that I ran slightly faster.

In preparation for the marathon, I ran between 80 to 110 miles a week, which included two workouts (usually an interval session and a tempo run), and a long run every Sunday. My long runs started at 16 and gradually increased to 22 miles. I learned that I ran best when my training was balanced and when my mileage was moderate. I think I ran best when my weekly mileage averaged of 80 to 90 with quality workouts.

So much of training is trial and error and you really don’t know how your body is going to respond until you’re actually doing it. And even after all of that training, I had no idea if I would even finish the marathon. It was an unknown. It was a leap of faith. The marathon might very well be the only distance that you can’t actually run before the race. You can run shorter distances at goal race pace, and you can run long runs of 22 miles or more at a slower pace, but you really don’t know if you can maintain your goal pace for the full marathon distance until race day.

While finishing fourth was a strong showing for my first marathon, I believe I could have run faster. The winner was only one minute ten seconds ahead of me. And, just like in the Olympics, I believe there were things I could have done differently in my preparation that would have allowed me to run faster. Elite athletes are rarely satisfied with their performances.

Out of all your successes and achievements in running and athletics what stands out to you as the most memorable?

I have always said that my motivation to run began with a very simple goal; how fast can I run from here to there? Whether it was the 100m dash or the marathon, the goal never changed.

The reward of running did not always come with winning, rather it came during the moments when I achieved something I didn’t know I could do. Sometimes that was a win, but most of the time it was a personal best, or conquering a hard workout, or just feeling strong during a long run. My most memorable race was making the Olympic Team in 2000, but not for the reasons most people think.

I had been injured for nearly seven weeks before the 2000 Olympic Trials. I could barely run at all. In fact, I couldn’t actually run until just a few days before my race. It seemed impossible; fly to Sacramento and try to make the Olympic Team when I have missed so much training?

I had IT band syndrome, which made bending my left knee painful and I could not even jog for ten minutes before the injury shut me down. I could run only one interval on the track before I boarded the plane for CA. But I thought to myself, the race is only one interval. Once I stopped running, I couldn’t start up again. I had to run a semi-final race first, and the fast pace was a total shock to my lungs and body. I hung in there, and I am not entirely sure how I did it. But I made it through to the final.

On the day of the final, there was a brief moment when they called us to check-in that I thought I would pull out of the race. I couldn’t even jog to warm-up. This injury challenged everything I thought I knew about racing. It challenged my own thinking and it challenged what I believed was possible and what was not.

Needless to say, I did check-in for that race, and would finish third, earning a spot on my first Olympic Team.

Marla pictured at the 2002 Prefontaine Classic, Hayward Field, Eugene (photo Victah@Photo Run).

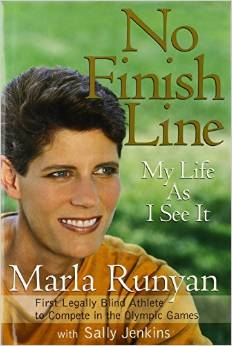

What can readers expect from your autobiography No Finish Line: My Life As I See It and how did you find writing your life story?

I co-authored my autobiography, No Finish Line, with Sally Jenkins and it was published in 2001. The process was a bit intense and it required that I reflect on moments in my life that I had not given much thought to. Most of all, it forced me to really think about my own visual impairment and find the words to describe how I see to others.

Since I have downplayed my disability my entire life, it was difficult for me to draw attention to it and actually call it a ‘disability’. One night, however, I recall sitting down at the computer and describing in detail how I saw the world. I wrote about the moment I discovered the dark splotch on the ceiling of my bedroom when I was nine. I told my mom that there was a ‘stain’ on my bedroom ceiling. She looked at me and said, “No, Marla, that is the scar tissue in your eyes”. She was right. When I looked at solid surfaces, the splotch really stands out, but when I look at objects or people, it becomes something of an abyss; just an empty space where everything disappears.

The process of reflecting and retelling the events that transpired in my pursuit of the Olympics also made me realize how lucky I was. So many people have come into my life even if only for a short time, and they all played a role in the person I have become. My parents were especially significant in my life, and this became more apparent to me as I wrote the book.

Could you tell us about your work as a teacher and ambassador at Perkins School for the blind in Massachusetts and if you had to some up the message you try to pass on to those you work with what would it be?

I currently teach assistive technology at the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, MA. I work with high school students and teach them to use technology to support their access to their education as well as develop their social communication skills and independence.

My students don’t think of me as an Olympic athlete – they just think of me as ‘Marla, their computer teacher’. That’s just fine with me. The goal of our time together is all about them – helping them to be successful in school and beyond. Even though I am teaching ‘technology’ skills, there really isn’t a day that goes by when I am not also teaching life skills – how to advocate for yourself, how to communicate with others, how to make good choices, and how to problem solve.

I believe that self-determination is at the foundation of everything we do. You can learn skills and you can acquire technology, but you must determine how you will use your skills and tools to achieve your goals. You also must know how to deal with setbacks.

I try to be a model for my students. What I want them to know is that nothing worth having is going to come easy. They have to work for it. They have to be good problem solvers. And they have to advocate and take the initiative to achieve their goals.

Despite Marla’s successes in running she is just as comfortable teaching and today spends much of her time in a classroom.

Do you have any exciting plans for the rest of 2015 and beyond?

I am still getting settled here in the Boston area. My day is full with work and being a mum to my nine-year-old daughter, Anna. However, I am also the type of person who seeks challenge and is always interested in learning something new.

Currently, I have been working with my colleagues at the Perkins School for the Blind reviewing the accessibility of specific websites and online courses. Accessibility consultation has developed my interest in instructional design of online course content, the concept of universal access of online media, and other domains of educational technology. I am not sure where this new interest will take me, but I do know that it is in my nature to keep moving forward in life – to set and work towards new goals – because there really is no finish line.

To find out more about Marla go to www.marlarunyan.net or