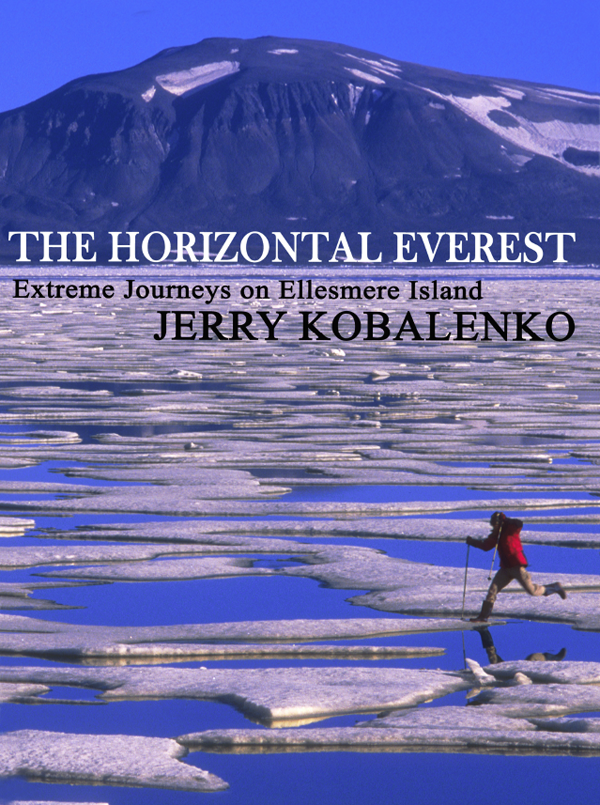

PROFESSIONAL photographer and writer Jerry Kobalenko specialises in northern adventure. His writing and photography have appeared in hundreds of publications around the world and his two books, Arctic Eden and The Horizontal Everest, have drawn plaudits from far and wide.

In this candid interview he tells us how his love affair with the Canadian Arctic began and why his favourite expedition partner is his wife, Alexandra.

Our final question to Jerry, asking what career he would have pursued had he not chosen the path he is on now, he was unable to answer…

Could you give us some background on your life and how you got involved in northern adventure?

Sometimes you consciously pursue your passions, but other times they pursue you. I grew up in Montreal and had little experience in the outdoors. Then one winter, I went up to an unheated family cottage for a weekend, and the temperature dropped to minus 40. By stacking quilts, I was able to pass a comfortable night. This gave me confidence that you could actually live in those temperatures.

I’ve always been physically restless, having to work out less for health than just to be able to sit down peacefully for part of the day. At the time, I was a marathon swimmer, racing each summer weekend between five and 15 miles. One day, I came home with the largest backpack I could buy; I wasn’t sure why. I began to pore over topo maps in the library. Gradually it dawned on me that I wanted to do an extreme winter expedition. I focused on Labrador, which was the wildest, most charismatic place an inexperienced young guy from Montreal could imagine getting to. The Time-Life book series on The World’s Wild Places even had a volume on Labrador.

Researching outdoor gear and winter travel as well as I could, I began to prepare for this trip. I decided I would ski 600km across Labrador in January and February, although I’d never skied before. A book on winter camping that I’d read had a small section on using fibreglass pulks, specifically those made by a guy in Minnesota. I contacted him and ordered a sled of my own.

My first attempt, I only got halfway. I fell through the ice and nearly died. It was a rookie mistake, completely avoidable. But I was comfortable out there at minus 40 and minus 50, and able to travel 15km a day, so I felt the conception wasn’t wrong. Careful preparation and fitness make up for a multitude of shortcomings in other areas.

I tried again next year and made it all the way. By the end, I’d fallen in love with sledding and with the north.

You’ve been travelling with your wife, Alexandra, since 1999 and even spent two months alone hiking the High Arctic in 1999 as your sixth date. What’s it like being able to share the experiences with your soulmate?

At the beginning, friends and relatives figured that she’d travel with me once or twice, during our courtship phase, then wise up. But she’s continued to join me on the summer journeys, because she gets something out of them for herself. She enjoys the intense immersion, the concentration, the isolation and especially the experiences with wildlife. She’s even fearless at chasing off polar bears.e

She’s my favourite partner not just because we’re married, but because she’s so good out there. She enjoys herself and does what it takes: she prefers to take her time, but if we have to paddle 60km in a day to get around a long stretch of cliffs, she does. Like any good traveller, she never complains.

An Inuit friend tells me that that’s one of the lessons that elders teach the young: never say a negative word when you’re out on the land.

You have written two Arctic adventure books – Arctic Eden and The Horizontal Everest. What can readers expect from the books and have you always had a passion for writing?

The passion for writing preceded the passion for travel and for the Arctic. I studied science at university but never wanted to pursue it. I wanted to write, and after graduation, that’s what I started to do.

My big break came after that first expedition in Labrador, when I wrote an article about it for an outdoor magazine. The editor liked it so much that she offered me a job as a staff writer. Things took off from there. My books tell stories about my travels, but also about other people’s Arctic adventures, both modern and historic. The books are about the place rather than the author and his derring-do. I may travel hard, but the tone is more curiosity than hairy-chested endurance of suffer-fests. Often I try to use my experience to reinterpret explorers’ travels. Because I’ve both done my homework and have a unique boots-on-the-ground experience, historians often consult me for their own Arctic work.

You are a professional photographer which must fit perfectly with your adventures and hikes. What’s it like being able to capture the magnificent backdrops and scenery you see and has there ever been a setting too beautiful to take a photo of?

Photography is easier and less frustrating than writing. Also, it forces you to be out there. Writers can lock themselves away in a cork-lined room, but you can’t take landscape photos that way.

Adventure photography appeals to the extroverted side of one’s nature; writing, to the introverted. There are lots of great scenes that just don’t lend themselves to a 24x36mm rectangle, or to any format. The Arctic, in particular, is often dominated by long horizontals and short verticals. These thin strips don’t look great as photos.

What advice would you give to someone wishing to explore the eastern Arctic?

The biggest hurdle for me has always been the cost of Arctic travel. I travel a lot and don’t fundraise – the fundraisers tend to spend years planning one big trip – so I have to do things on the cheap. The Arctic was never an easy destination, but transportation has become a lot more expensive in recent years.

The High Arctic – the lovely Ellesmere Island area that I’ve written about in those books – is almost unreachable now except for those with deep pockets. I have projects I’ve wanted to do up there for years, but I can’t, because expeditions that used to cost $2,000 or $3,000 would now require $30,000 – most of it for the charter aircraft.

So in recent years, I’ve re-focussed on Labrador, which is difficult but still affordable.

What’s your most recent expedition?

I’ve kayaked the entire Labrador coast from north to south and also manhauled the interior in winter from tip to tail except for a 400km section in southern Labrador.

In February, a friend and I completed that missing section in 34 hard days.