BRIAN MILTON is a journalist and adventurer whose first major expedition was in 1968 when he drove an Austin 7 across the Sahara Desert to meet his fiancé.

Having gained an interest in hang-gliding it wasn’t long before he made the progression to microlighting and today is well-known and respected around the world for his success in the sports. He has won multiple awards for his achievements and in 1987 his flight in the Dalgety Flyer (a shadow 3-axis microlight) from London to Sydney was at the time the longest microlight in history. He also founded the National League of Hand Gliding which took Britain to world dominance in the sport.

In this exclusive interview Brian talked to us about his successes in the sky and career in journalism as well as the story of his first wild adventure.

You are known as one of Britain’s greatest adventurers. When did your passion for expeditions and the outdoors begin?

I spent nine weeks ‘on the road’ in the US in 1964 – the year the Beatles arrived in America – jumping freight train, sleeping under freezing motorway bridges, and ended up 300 miles inside the Arctic Circle in a DEW-Line station called Bar-4, washing dishes for $100 a week and found.

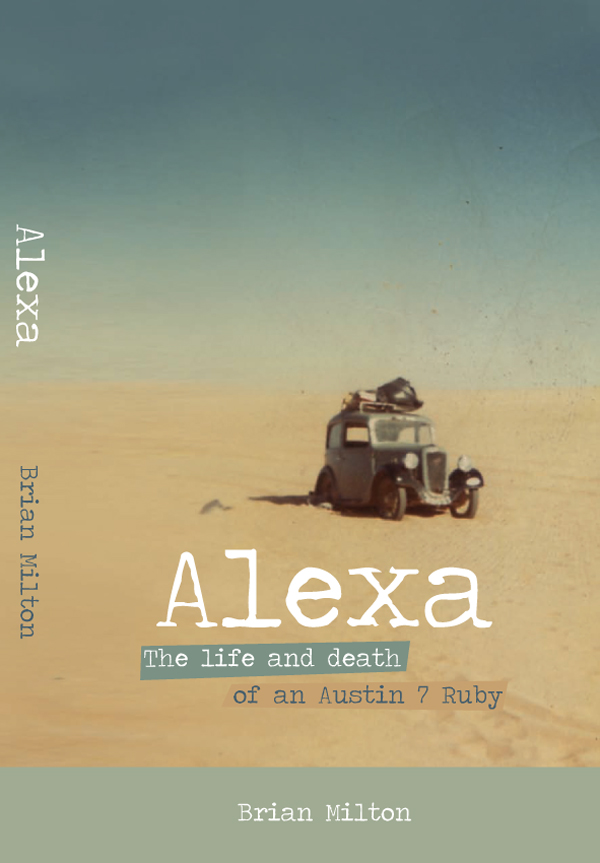

Four years later, having fallen in love with a colonel’s daughter called Fiona Campbell, when she went to see her South African birthplace which she had left as a three-month-old, I resolved to marry her, and set off in my 1937 Austin 7 called Alexa to claim my bride.

I drove it across France and Spain and north Africa, crossing the Sahara Desert in 18 days, and driving on down through the Congo. Alexa didn’t make it. I crashed once in the Sahara as a result of ptomaine poisoning, and ran out of water twice.

Later I drove 2,000 miles on three pistons – no plug in the fourth – and 900 miles without any brakes, lights, shock absorbers, starting handle or starting motor. I did attend the consecration of a Congolese Bishop, and later that evening, ‘drank for England’ being among the last three white men standing (I still remember the following day’s hangover).

The book I wrote about this adventure is called Alexa – The Life and Death of an Austin 7 Ruby which can be found on my website here.

I was thrown out of South Africa on the night Fiona and I were writing our wedding invitations. Three years later I started as a BBC Radio freelance reporter.

What were your early experiences of hang-gliding and when did the progression to microlighting start?

I recorded a story in October 1974 with Brian Wood, the British hang-gliding champion, who flew for eight hours 30 minutes on Rhossilli Cliffs in Wales. At the end of the interview I said I would make a half-hour programme about hang-gliding if he would teach me to fly.

Back then they took you to the highest hill they could find – Devil’s Dyke near Brighton – told you how to control the wing – push, pull, lean left, lean right – and when the wind wasn’t too strong, they threw you off. You were expected to learn in the minute before you hit the ground.

I immediately went up for a second go, and after that, was rigging for a third go when someone said, ‘it’s dark’. Night had fallen. I bought a hang-glider that night.

Microlighting really started in England in 1981, sticking an engine on a ‘rag wing’, but I was experimenting in 1978, intending to fly a powered hang-glider to Paris. There is some startling footage to be found on my website www.brian-milton.com five minutes 30 seconds into the minute-minute video ‘Wind, Sand and Stars’ of me falling 250 feet in such a wing. It happened on Monday, November 13, 1978, at 3.15pm, and one result is that I gave up smoking. Another result is that I was so frightened of flying with an engine that it took me six years to have another go. I couldn’t stand being a coward.

For those who aren’t aware could you explain the main concept of microlighting?

We are going through a second history of flight. Most people date the start of mainstream aviation as December 17, 1903, when the American Wright Brothers first flew. There has been a mainstream history since then, Bleriot crossing the Channel, the first London/Paris race in 1911, huge development in World War One, Ross Smith flying England-Australia, and Alcock and Brown crossing the Atlantic in 1919, the first world flight in 1924, Lindbergh making the first New York-Paris flight non-stop in 1927, World War Two, jets, going to the moon in 1969.

By then a group of ‘holy lunatics’, mostly American, were experimenting with foot-launched flight, after the real ‘Father of Aviation’, the German Otto Lilienthal, who was killed in 1896. They had a meet on May 23, 1971, on dunes in San Diego, California, on what would have been Lilienthal’s 123rd birthday – google ‘First Lilienthal meet, May 23, 1971’ – in which the longest flight made that day was 196 feet, and the longest time in the air was 11 seconds.

Since then we have learned to fly in a different way, and are exploring all the original aviation records of the mainstream, but we are doing it in the ‘new aviation’. Twenty-seven years after the Lilienthal Meet, in a direct descendent of the Rogallio wing which flew that day, one of us flew around the world. It happened to be me.

You were the founder of the British National League which took Britain to world dominance in the sport. Could you tell us more about the formation of the League and what it meant to you to be able to see your efforts achieve so much?

I came second in the British hang-gliding championships in 1976, and a fellow called Bob Wisely came first. Neither of us were the first or second best hang-glider pilots in Britain (by a long shot).

I had joined the governing Council of the BHGA, essentially to stop the World hang-gliding championships being held in Apartheid South Africa in 1977, but because I thought competition was so unfair, I took it over.

Forming the League was my way of apologising for depriving British pilots of a trip to the Worlds. One effect was to break the power of the regional manufacturers, as the best pilots in the country met five times a year, and flew pilots’ tasks. If they were sometimes dangerous, it was fair because I flew all the tasks myself, so if they were difficult, other pilots said, “well, if Milton can do it, so can I”. We ran the first open cross country championship in 1978 – ‘go as far as you can, as often as you like, and you get double marks for the day’s flying’.

Another result is that we went to the USA in the first American Cup in 1978 – our opponents were the Canadians, the Japanese, and the mighty Americans – and thrashed them all, winning seven of the nine tasks over the Americans. The eight British pilots placed first, second, third, fifth, sixth, seventh, 12th and 24th. It was tighter the following year but we won that too.

Having won the American Cup you were awarded the Prince of Wales Trophy in 1979. What did that award to mean to you?

In 1980 the Americans produced a superkite called the UP Comet, a real generation change, and banned the sale to any British pilot, so they won that year. It was for the first victory I won the Prince of Wales Cup from himself.

You went on to break more records in microlighting and flew all around the world setting yourself newer and harder challenges. What have been some of your most memorable successes and some of your own personal highlights?

I chased the ghost of Ross Smith from London to Sydney in a three-axis microlight in 1987/8, overcoming odds of 50-to-one suggested by the Australian ‘father of hang-gliding’, Bill Moyes.

I was sponsored by a foods group, Dalgety, which had roots laid down in 1840 in Australia. A lot happened on the flight. I was wrecked on a Greek island but glued it together in six days and flew on. There were out-landings in Jordan, three in Saudi, but I also came under the patronage of Jordan’s King Hussein.

One result was when a fuel blockage put me into the Persian Gulf on Christmas Day, 1987, 32 miles from shore, the local Arabs were very helpful. I was plucked from the sea, found my mechanic – Mike Atkinson, with a first-class airline ticket to Sydney – and we went back six hours later and rescued the Dalgety Flyer.

Mike carried a Rotax 447cc engine as hand baggage, and we got the aircraft to fly again five days later, and I flew on.

There were other adventures, but I made it to Brisbane by the BiCentenary – it was an official Bicentenary event, and later to Sydney.

It was, for nine years, the longest, fastest microlight flight inn history, but dismissed by the editor of Microlight Flying, a non-flyer called Norman Burr, as ‘the world’s longest ego trip’, and as a result, a year after the flight ended and nine months after I returned home, not one British microlight club invited me to talk about the flight.

I was invited to one of the two iconic annual dinners hosted by 617 Dambuster Squadron though, – and later with Tony Iveson DFC, one of the men who sank the Tirpitz – went on to write ‘Lancaster – The Biography. My account of the Dalgety flight, published by Bloomsbury, later Harry Potter’s publisher – is now out of print, but may be found on Amazon.

The ITN half-hour programme called On a Wing and a Prayer and a Sponsor can be found on my website here.

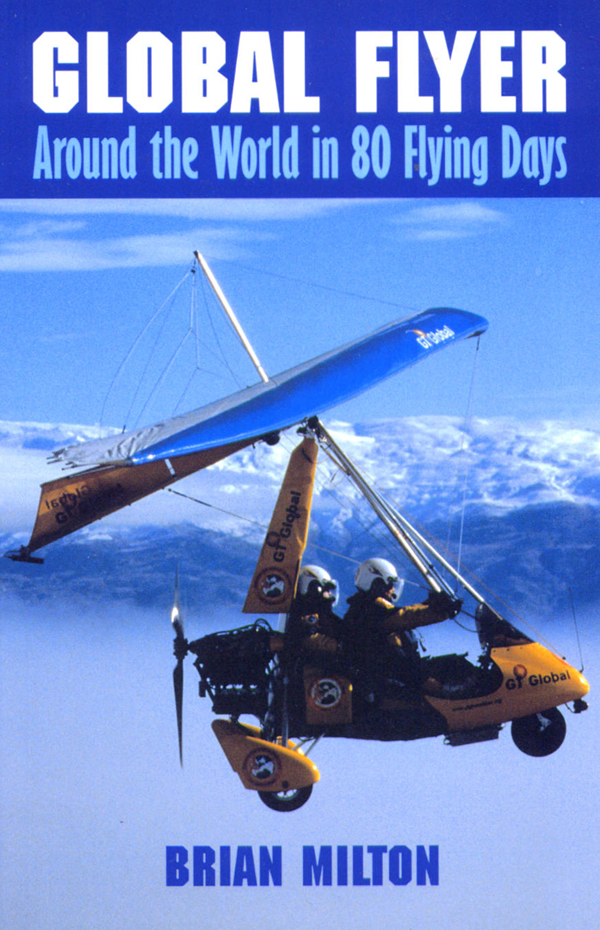

Because no one in my peer group actually looked at the Dalgety flight, ten years later when I set off on my attempt at the first microlight flight around the world, I was not given than much chance of success. I well-remember the great woman pilot, Judy Leden, saying, as I returned “there’s a great deal of hat-eating going on right now”.

What did it feel like to win the Britannia Trophy in 1998?

The Britannia is the highest award in the gift of the RAeC, and I won it from Prince Andrew for the world flight. I could not persuade him to to sit in the trike for a photo. There are still copies of the book I wrote about that flight, Global Flyer, £10 in paperback, available on my site. I am also writing a film script for a Hollywood producer. Four half-hour TV programmes, called A Microlight Odyssey were shown on National Geographic TV.

Could you tell us more about the books you have written?

I wrote about a failed attempt at flying the Atlantic by microlight in 2001. It’s called Chasing Ghosts, and a TV programme, and a book, can be found on my website. If there’s a proper publisher out there, I have written at least 14 books, and I am looking to get them published as a set. The latest, called In Defence of Mischief carries the real inside story of the students who parked a pre-war Austin 7 on the Senate building in Cambridge in 1958. It also has an account of trying to fly through the Ark de Triomphe.

You have spent much of your life working as a journalist. Has that been mainly in sport or other interests?

I was a general reporter for many years, ten of them with BBC Radio, including being an editor for nearly two years. I spent 15 years in TV, once as an industrial reporter, covering the Miner’s Strike ion 1983/4, and later as a financial journalist. I was, for example, editor and main presenter of the half-hour daily financial programme, European Business Today.

Do you still fly and how has microlighting changed since you first started in the sport?

I still plan adventures, and still believe I will raise the money to make them work. Paperwork in microlighting is fast-approaching that in mainstream aviation, and will choke microlighting to death, sadly. I am glad to have had the best years.